The Long War #49

Judging generals, mobilizing the working class, entering Ukraine from Belarus, derussifying Odesa & more

KYIV—It’s an understatement to say that a lot has happened since this newsletter last went out in early January. So let’s just dive in: you’ll find in this issue four interesting stories (about the arrest of Ukrainian military officers; Ukraine’s working class; about the trip Ukrainians looking to leave the occupied territories are forced to endure; and about the controversial derussification process in Odesa) and my thoughts on why I think these stories matter.

Then, I wrote a bunch of disjointed reflections about the recent weeks, the negotiation process, and about whether the Russian population’s initial disbelief in the first hours of the Russian invasion can tell us anything about Vladimir Putin’s willingness to end it.

I’ve also recently written for the Financial Times a story about the domestic repercussions of the Trump-Zelensky clash which you can read here.

Stories

Graty (in Ukrainian & Russian) | Case of the Kharkiv border breach: what does the investigation and the suspects say | March 13

Some detailed court reporting from Ukrainian outlet Graty about the first criminal case targeting Ukrainian military officers. Back in January, law enforcement detained brigadier general Yuriy Halushkin and two of his subordinates (lieutenant general Artur Horbenko and colonel Ilya Lapin, who were at the time respectively commanders of the 125th brigade and of an infantry bataillon of the 23rd brigade). All three are accused of dereliction of duty during the May 2024 Russian offensive in the Kharkiv region.

It would be too long to just recap Graty's piece, but an example of one accusation makes it clear how specific and granular the accusation is:

The investigation claims that the general deliberately assigned to previously mentioned units defense areas that they were unable to defend. The accusation states that the units did not have tanks and armored combat vehicles, and were not staffed with fighters. In particular, the 415th battalion was staffed to 55% of its full strength, and the 172nd and 215th - 66%. In addition, the general did not reinforce them with the above-mentioned five brigades, with which he strengthened the second echelon of defense, and also did not control the conduct of the battle by the commanders of the units that withdrew without orders, etc.

[...]

Colonel Ilya Lapin told "Graty" following the hearing that he is being tried for withdrawing his fighters from positions on May 10 without a direct order from a senior commander. However, he believes that he did the right thing, because he saved the men, took them to a second position, and reinforced the positions of the 1st and 2nd companies that were advancing there. "I made a decision, I am now responsible for this decision. Human life is the most important thing. There will be people - there will be a state and there will be victory," said Lapin.

The investigation, arrests and now hearings have had deep political implications, as the quest to find someone responsible for the Russian advances into the Kharkiv region last year quickly clashed against the need to maintain troop morale and avoid the implication that any retreat could lead to an arrest for the commanding officer (something with heavy Soviet undertones). Ukrainian opposition figures such as Petro Poroshenko seized on the scandal to denounce the authorities, and there’s definitely been a general unease about the procedure.

LINKS | Daria Saburova: ‘We must take an interest in the complex realities of Ukrainian society’ | March 9

A thought-provoking interview about the way Ukraine's working class in the industrial city of Kryvyi Rih (where Volodymyr Zelensky grew up) mobilized after the 2022 Russian invasion. Among many other things, it serves as a reminder of the massive but often underrated role that non-professional volunteers played in this war. Saburova’s research also highlights the important point that a lot of people who decided to organize themselves in order to confront the Russian invasion did so with different views from what I'd call (a bit reductively, I admit) the ‘Kyiv consensus’—from language to historical references to economic reforms.

Novosti Donbassa (in Ukrainian & Russian) | Belarus' "white passport" for Ukrainians: testimonies from those who crossed the border | February 26

Over the past three years, the movement of Ukrainians to and from the regions occupied by Russia never fully stopped. It was relatively easy for only a couple of months, when a corridor through the frontline allowed convoys of cars and trucks to enter and leave Russian-controlled Ukraine in the Zaporizhzhia region. That route closed in the fall of 2022, after Moscow officially annexed the region and a strike on the place where the convoys gathered killed several dozen people (I wrote about it in The Long War #10).

Later, a new crossing point was opened in the Sumy region. When fighting intensified in that area, it was moved 800 kilometers West, on the border with Belarus (and just 60 kilometers from the Polish border). Fleeing the occupied territories now involves a days-long, expensive, dangerous and exhausting trip through a war zone, then Russia and Belarus (that's without even getting into the stories of people who, for various reasons, want to go to the occupied territories from Ukraine and have to endure filtration at Moscow airport).

Now, Ukrainian outlet Novosti Donbassa (ND) reported in late February, Belarus has introduced new rules for Ukrainians looking to enter Ukraine from Russia or the occupied territories of Ukraine at the Mokrany-Domanov humanitarian corridor. It isn't a border crossing point—only Ukrainian citizens can use it, they can only cross on foot, and only from Belarus to Ukraine.

It used to be, ND writes, that Belarusian border guards would let Ukrainians cross with any official Ukrainian document, such as a driver's license, ID card or birth certificate. But they now require an actual passport, which many Ukrainians do not have. Hence the "white passport", the nickname of the "travel document for return to Ukraine" now delivered by the Ukrainian consulate in Minsk (keep in mind that just getting to Belarus is near-impossible if you don't already have a Russian ID). The procedure can take up to a month, forcing Ukrainians to find lodging in Belarus for several weeks after an already grueling trip.

I’m highlighting this story for a specific reason: negotiations have now begun which, if successful (a huge ‘if’) would leave under Russian control the parts of Ukraine currently occupied by Russia. I recently did an interview with a representative of Zmina, a Ukrainian NGO dealing (among other issues) with the fate of Ukrainians living in occupied territories. Alena Lunova insisted that, in such a situation, negotiators should at the very least fight to reintroduce easier ways for people to leave the occupied territories, as well as prevent Russia from forcing Ukrainians living in occupied territory to get a Russian passport. But while humanitarian issues such as prisoners or Ukrainian children deported to Russia has already been raised, I don’t think there’s still been any discussion about making it easier for people to either leave or travel between the occupied and non-occupied regions of Ukraine.

Ukrainian Moderna (in Ukrainian) | Oksana Dovgopolova: "Our work in the field of memory should be directed not at Russia, but at ourselves" | February 6

This interview of Oksana Dovgopolova, a Ukrainian researcher specializing in memory issues, is the most interesting piece I’ve read about the ongoing feud surrounding the fate of Odesa monuments linked to the city’s imperial and Soviet past. I’m highlighting a couple of selected quotes, but I encourage readers to put the entire interview through a translation engine:

When it came to dismantling the monument to Catherine II, it was easier because it is only one object, and it wasn’t part of the urban space before. This monument was installed in 2007, that is, it was not there from 1920 to 2007. It was a newly made figure with no historical value. The procedure for demolishing this monument went quite smoothly, because it did not affect the everyday life of the townspeople.

But the processes currently taking place have a significant impact on people's everyday lives. For example, there is a process of mass renaming of streets, and not everyone is ready to accept such a radical reboot of the city's cultural space. This is not due to the fact that there are some pro-Russian people inside Odesa.

[...]

— What historical figures or topics cause the most controversy?

— The biggest debates revolve around Alexander Pushkin and Isaac Babel. The “Pushkinopad” [movement of taking down statues of Pushkin] has been ongoing since 2022 (it began earlier, but acquired a massive character precisely in 2022). In Odesa, a rethinking of the figure of Pushkin is needed, because in fact, rational arguments are expressed by both sides of the conflict. The monument to Pushkin in Odesa was not erected by Soviet authorities. It’s not like a Pushkin statue in, say, Mukachevo, where nobody knows how it got there and everybody understand that it is a clear marking of the space by Soviet authorities.

On the other hand, the position of those who say that it is now impossible to keep a monument to Pushkin in the space of any Ukrainian city —no matter how it got there— is absolutely understandable, because it is a marking of the Soviet/Russian imperial power. Unfortunately, in our country, any object in public space continues to be perceived exclusively in the context of the glorification of a certain regime. The idea that an object can be redefined does not exist, because there are no successful examples. And people cannot find a common position, because their views are fundamentally different.

The same situation applies to Isaac Babel. By the way, the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance admitted the renaming of the Babel street was illegal, because he has no connection to the NKVD, which is what he was accused of. There are no documents confirming this fact. Therefore, in Odesa, on the one hand, a movement is spreading in defense of this figure, and on the other, voices are being raised to remove the monument to Babel. Another aspect, not related to the NKVD, plays a significant role here: Babel is accused of developing a version of the myth of Odessa as a bandit city, as a city of gangsters, that is, researchers of the Odessa myth have been fighting Babel for a long time.

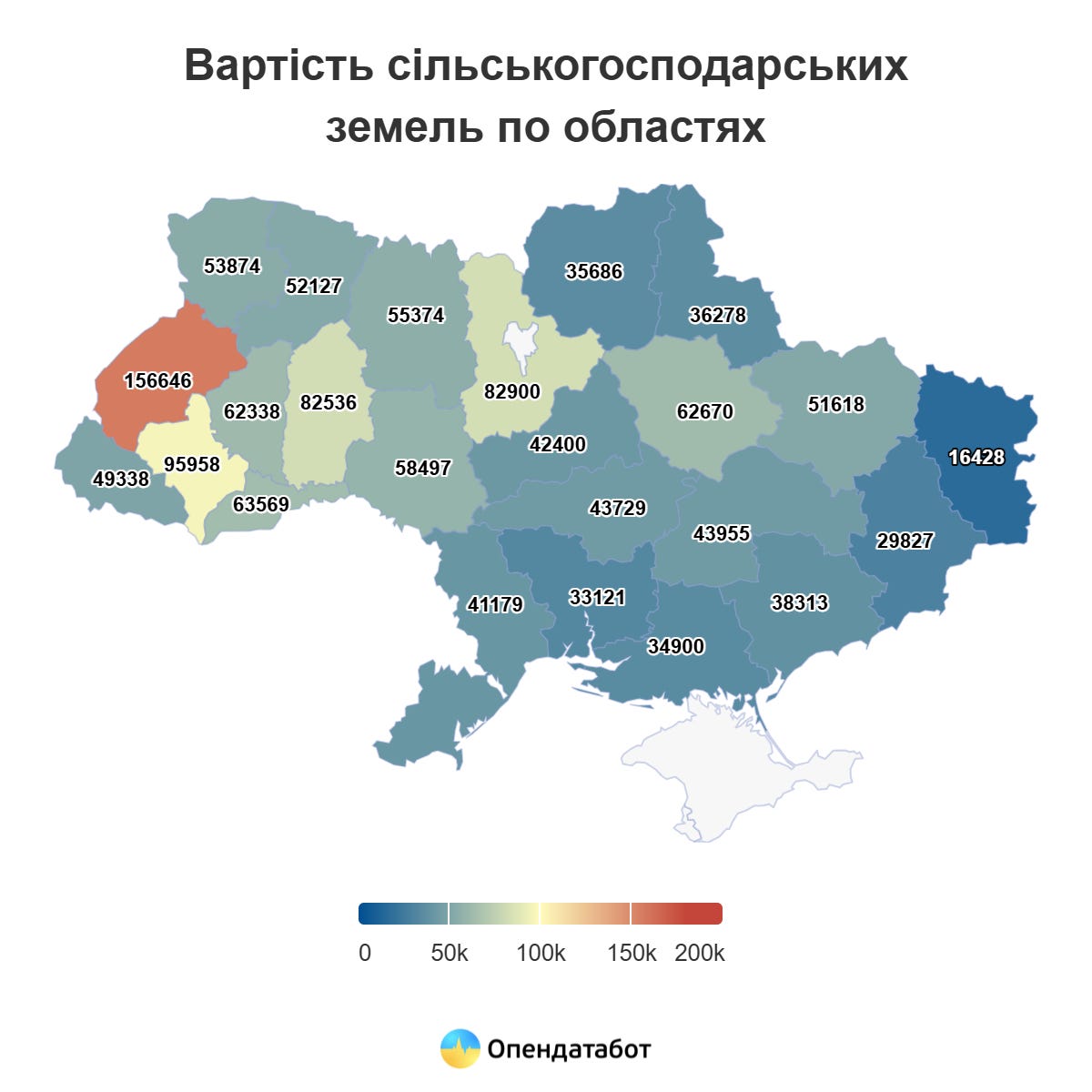

Picture

Yet another indication of the great Western shift that Ukraine has undergone since the beginning of the Russian invasion: agricultural land is now consistently at the highest price in Western Ukraine. In early March, one hectare of land in the Lviv region was 3 times more expensive than in the central and agricultural region of Kirovohrad (prices have since gone down in the Lviv region, but the general trend seems to hold).

Thoughts

On time

A month ago, Ukraine commemorated the third anniversary of the Russian invasion. It only struck me a couple of days ago how long three years really is. At a very personal level, I’ve now lived in Ukraine for almost as long post-invasion as I did before (I had been a Kyiv-based correspondent from early 2018 to early 2021, and settled back in Ukraine in August 2022). More generally, the first Russo-Ukrainian war arguably lasted one year exactly*, from the February 2014 annexation of Crimea to the February 2015 Minsk 2 agreement. The war didn’t stop then of course, but kept going as a simmering conflict that, even in Ukraine, started fading into the background. Three years of such a violent and bloody war is really hard to process. It becomes even longer when you look at it from the perspective of teenagers, as I did for a recent story, kids who were just 15 or 16 when the invasion started, who are now entering university and, if they’re boys, cannot legally leave the country anymore. Three years and already a youth irreparably damaged.

(*I realize this a bit of an uncommon view, but I do think that, while there is of course a strong continuity in the events from 2014 to today, there are three distinct periods running from February 2014 to mid-2015; from mid-2015 to February 2022; and from February 2022 to the present day)

On negotiations

Being a correspondent living in Kyiv, the most striking feature of the recent weeks of Ukraine-US-Russia negotiations is how far from Ukraine it’s been happening, something that has translated to working on the phone and behind the laptop rather covering the story on the ground. I don’t think it is necessarily ominous in itself (negotiations happening in the country of a third party is pretty standard, after all) but it does add to the growing sense that things are now being decided outside of Ukraine.

On surprise, Russian society and ending the war

One aspect of this war I still think about three years on is how, even a few days before the first Russian tanks crossed the Ukrainian border, Russia as a whole—from the most conservative, pro-Putin figures to the most opposition-minded liberals—found the idea of a Russian invasion utterly ridiculous. Nobody in Russia believed Moscow would invade and, crucially, nobody believed it would be a good idea to invade. Then, when Russia did invade, most of the Russian population almost immediately accepted and (at least openly) supported the war.

I remember thinking that, even for a population broadly supportive of Putin, an outright, unprovoked invasion of Ukraine would be a step too far. I remember colleagues who said there wouldn’t be an invasion because there were no signs that the Kremlin was preparing its population to such an invasion by, say, ramping up the propaganda on its TV channels. And I wonder what historians will make of this, of the shock that Russian society experienced when the war began, and why that shock so quickly translated into support rather than revolt.

I think that shock was instrumental in getting the Russian population to accept the war—Putin didn’t just hope to stun Ukraine into surrender, but also the rest of Russia into compliance, a general fait accompli. That’s not to say there wasn’t any preparations: there was ten years of those, since the annexation of Crimea. Preparations that suppressed any desire to protest and even prompted thousands of Russians to call their relatives in Ukraine in the early hours of the invasion to tell them Russia was going to liberate them—or that they deserved what was happening after “bombing Donbas for eight years”.

Does that matter today? I’m not sure. I’ve been thinking that this could be yet another factor making Putin reluctant to a ceasefire: even a temporary end of the hostilities would likely be welcomed in Russia, particularly if it comes with the lifting of sanctions, and that relief could make it harder for Putin to restart the war. Putin’s reluctance to declare a new wave of mobilization shows well enough that he is sensitive to public opinion, after all. Putin wouldn’t be able to rely once more on the paralyzing shock of the initial invasion, meaning that stopping the war now would make it harder for him to start it again if he wanted to.

But then again, relaunching the war after a ceasefire wouldn’t be like starting it in the first place. The Rubicon has been crossed, the bell has been rung. So maybe that does not matter.